A frequently-asked-question by new investors is “where to invest money for beginners,“ or some form of this question. And because it’s such a popular topic, a quick search will get you a variety of recommendations, good and bad. What’s, unfortunately, less common though is an emphasis on the prerequisites (requirements) to know before investing.

I get it, people searching for “where to invest” most likely want to know where to invest! But this group also covers first-time investors, and first-time investors are unlikely to search for “what should I know before investing?” Although it’s a necessary first step, it’s the beginners who ironically don’t fully understand that. You don’t know what you don’t know, right?

To me, the lack of emphasis is serious because beginners become susceptible to bad advice or worse, scams. There will be no recommended investments or platforms in this post. These are 3 important things to know before asking where to put your money.

(This is one of the fundamental topics under personal finance. Should you find the discussion too easy, head over to the Intermediate/Advanced topics for a challenge.)

Page Contents

Know what ‘returns’ are (and that there’s a tradeoff)

What is a return?

Returns are what you get from investing, expressed in percentages. If you invest 100.00 and you get 1.00, your return is 1%. (Related: Finance for people who hate math)

Returns are usually in per annum (p.a.), as in per year, for comparability across investments. A traditional bank gives out maybe 0.5% p.a. in interest. That is your return for depositing (investing) in a traditional bank. Digital banks offer higher interest rates, 2.5% to 4% as of this writing in February 2021. Aside from time-horizon, different investments should also be compared in comparable terms (e.g., comparing after-tax returns with before-tax returns is wrong).

Short-term (i.e., less than one year) returns are also annualized for comparability. The idea here is a 6-month investment can earn another 6 months by reinvesting.

As investors, we naturally want to maximize returns.

There is always a tradeoff

You’ve also probably heard of the phrase “high risk, high return.” This is generally true. Higher risk investments such as traded stocks or private businesses offer higher returns, versus bank deposits, but you’ll have to bear the higher risk. As in, you risk losing your money in a business, and so are paid a higher return for bearing that risk.

(Here’s a quick tip the beginners can ignore: “High-risk high-return” should be qualified. In the stock market, for example, only the non-diversifiable risk is compensated. If you increase your risk exposure through diversifiable risks, you are not compensated and you shouldn’t expect a higher return for the added risk.)

If you decide to invest in a business, there’s a whole spectrum of possible scenarios – from over 100% returns to negative 100% and losing your entire investment. Stocks, as generally safer investments compared to private businesses, yield lesser returns. The common rule of thumb is for a buy-and-hold strategy to earn 10% p.a. in the stock market.

(Related: I also experimented on an application on the PSEi of the Buffett indicator earning 19% p.a. from 1998 to 2019)

Scams portray a no-tradeoff scenario

The tradeoff will always be there. If there’s an imbalance, economic forces will move towards rebalancing.

Here’s an extreme example to highlight the point. If running a business was guaranteed by the government then everyone would start a business because of the larger returns. Bank deposits would either cease to exist or be forced to offer comparable yields. Or if putting money in a secure deposit yielded 10%, why would anyone invest in the more risky stock market?

Scams like “get-rich-quick” schemes or “guaranteed to double your money” characterize a no-tradeoff situation. They promise large returns with not much tradeoff. As a rule of thumb:

If it’s too good to be true, it probably is.

And because there’s a tradeoff between risk and return, we want to maximize returns at risks tolerable to us.

What’s tolerable for you is for you to find out. But it’s also worth noting that risk tolerance can change. Mine certainly did. Running a business and reaping some of the rewards, turns out it wasn’t as bad as I thought.

(Related: The Risk and Return Trade-off Applied in Real Life (Uncommon Examples))

Know what a weighted average is

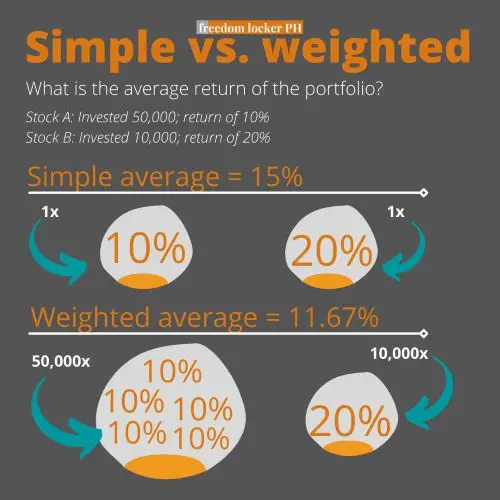

Simple vs. weighted average

A weighted average is an average that considers how much each item weighs. 🤷♂️ Sorry, still trying to come up with a better definition.

Let me try that again. The average we know from elementary is known as a simple average and weighs every item equally. On the other hand, a weighted average is swayed by large weights. Weights are based on how many times each number is counted.

For example:

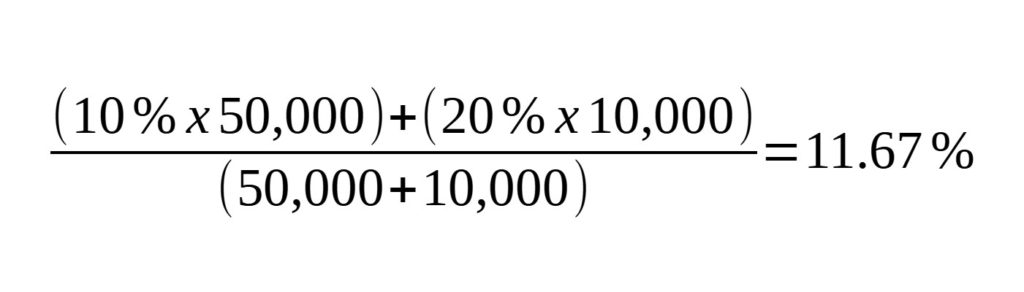

Stock A: Invested 50,000; return is 10%

Stock B: Invested 10,000; return is 20%The simple average is: 15%

Simple Average = (10% + 20%) / 2

Simple Average = 15%The weighted average is: 11.67%

It’s like this investor is investing 60,000 times. A weighted average is acting like 50,000 times the investor got a 10% return and 10,000 times got a 20% return. Because the 10% yielding investment (Stock A) is heavily weighted (50,000), the weighted average of 11.67% is a lot smaller than the simple average of 15%. If the weights were reversed and more was invested in Stock B, the weighted average would be higher than the simple average of 15% — despite owning the same stocks.

Portfolio returns

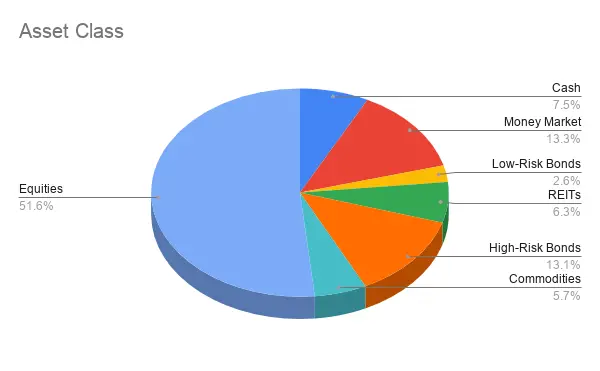

A portfolio is basically the collection of assets you hold. Your portfolio could include 100,000 in bank deposits, 500,000 in stocks, and 1million in real estate property. The total value of this portfolio is 1.6 million.

A portfolio’s return is a weighted-average.

Specifically, your portfolio’s return is a weighted average of your assets’ returns, with weights based on the amount you invested per asset. We want to maximize our portfolio returns.

(Does a free spreadsheet that calculates portfolio return interest you? Leave a comment and let me know.)

Know your goal (and risk-tolerance)

If portfolio returns are a weighted average of your assets’ returns, portfolio risk is not just a weighted average. Rather, portfolio risk also takes into account how your individual assets/investments behave together. (Or “correlation” in finance nomenclature. See Reduce risk in the stock market: Diversification Primer).

But as someone about to start, just know for now that higher returns typically come with higher risks. And then reflect on what your objective is for investing. If your objective requires a return of 10%, for instance, are you then willing to take on the associated risks with a 10% return investment?

This last step involves some introspection.

I hate to say it, but the best person to decide which investments to pursue is really yourself. You can fill out risk-profile forms and whatnot, but it’s ultimately your job to understand what level of risk you’re willing to take for a chance at higher returns.

Even outside of finance, the tradeoff apparently permeates. It would be foolish to withdraw yourself from understanding and expect excellent returns without the effort.

Are you excited or nervous for your first investment? Which assets interest you the most? Let us know in the comments.

Read more, select a topic: